Opium, the famous morphine-containing plant, is a globally recognized flowering plant most recognized for its use in opioid analgesics. 1 in 5 Canadians are prescribed opioids to manage chronic pain. The Opioid Crisis is responsible for 66% of the world’s drug-related deaths. The world needs another tool to manage pain.

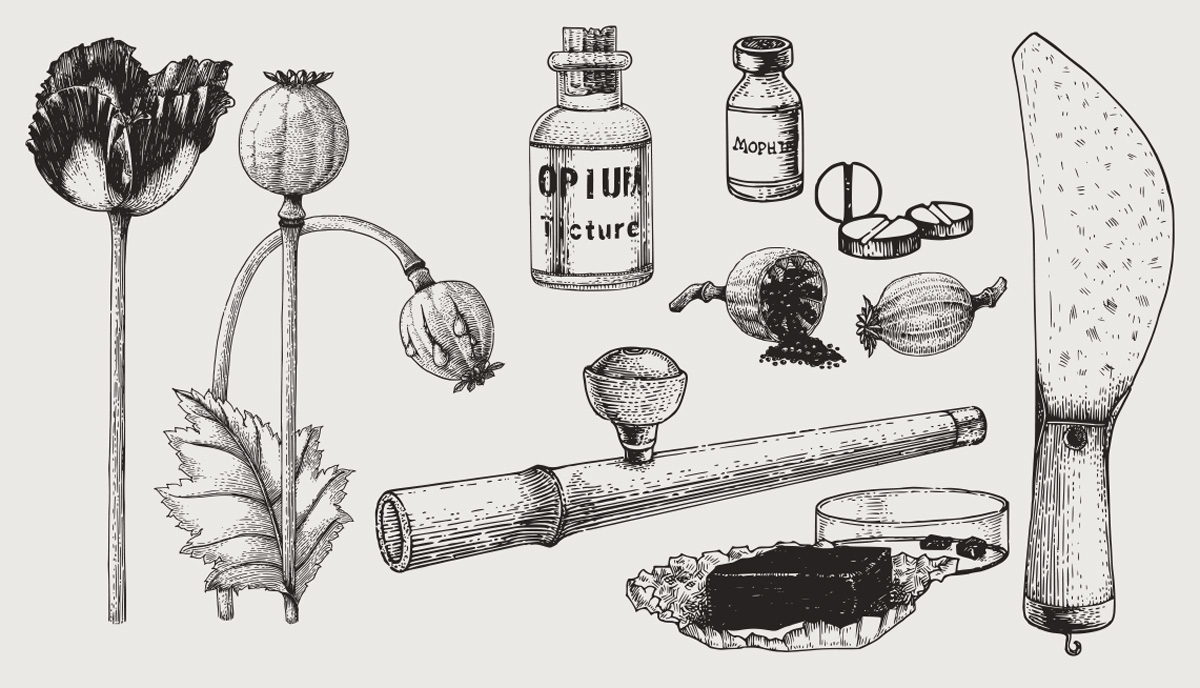

Opium is derived from the opium poppy Papaver somniferum. The plant is known for the white, red or purple flowers and their seeds, commonly used in baking. [1] When the poppy is ripe, incisions are made in the seed capsule and milky latex oozes out. This substance is then dried and oxidized to form opium. Opium contains dozens of alkaloids, which are responsible for the substance’s medicinal properties. [1,2] Naturally occurring opium is the precursor material for a class of medications known as opioids. Opium can also be further refined by changing its chemical structure to form synthetic or semi-synthetic opioids. [1]

The earliest reference to opium growth is in 6500 BCE in La Marmotta, Italy. In 3400 BCE, the Sumerian civilization referred to opium as “the joy plant” due to its powerful pain-relieving properties. [1] Ancient texts reveal opium was adopted by Greek and Roman physicians to treat insomnia, pain and severe diarrhea. [1] As the world learned about the plant’s benefits, demand increased, and many countries began to grow and process it themselves.

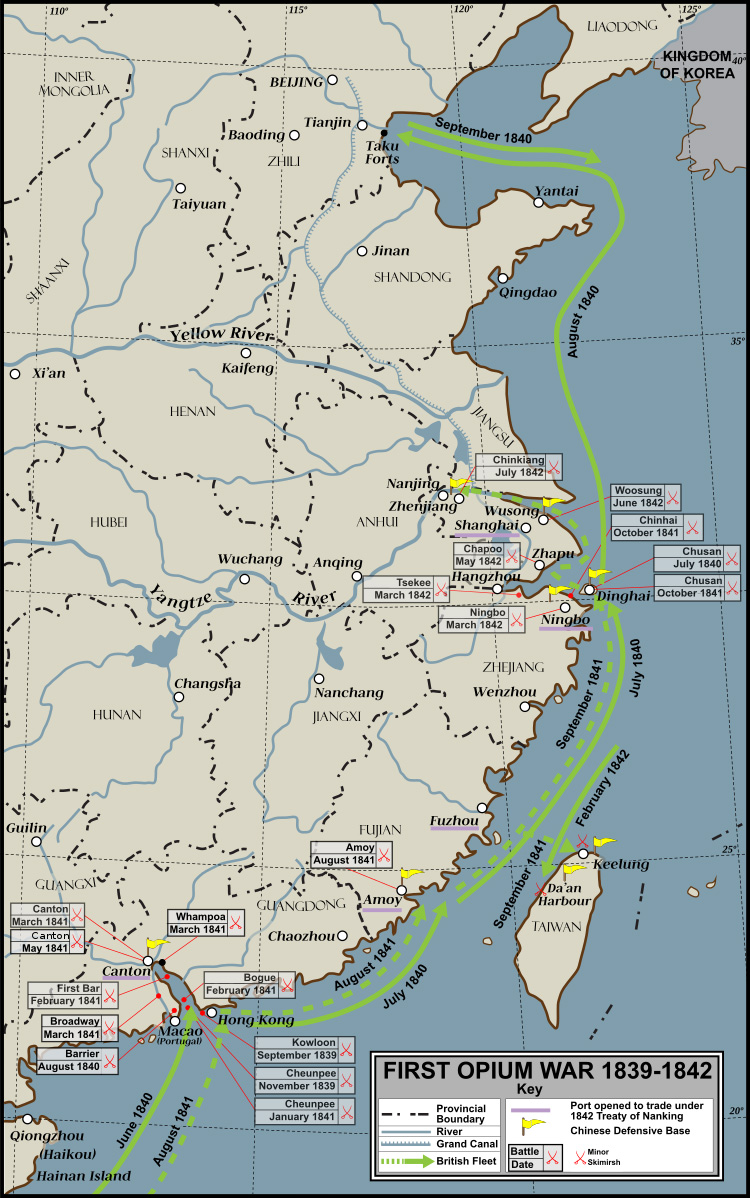

In the mid-1800s, Great Britain smuggled opium from India into China. As a result, opium addiction in China skyrocketed and all importation and cultivation was banned. [3] This led to the Opium Wars between European rulers, who wanted to keep opium trafficking routes open, and China, who wanted to suppress opium use. China lost both wars and opium addiction remained an issue. [3]

As thousands of Chinese immigrants came to America in the late-1800s, opium dens were established as sites to buy and sell the drug. [3] Morphine was the first active ingredient isolated from opium and was used as a powerful painkiller during the US Civil War. In the second half of the 19th century, heroin was discovered and was marketed as a morphine substitute and cough suppressant, which was even safe to use in children. [3] As a result of these medical uses, opioid dependence and consumption increased.

Today, opioids are used to treat acute or chronic pain, though sometimes they are used to treat moderate to severe coughs and diarrhea. [4] These medications are reserved for pain that does not respond to other treatment options, or if other options are not appropriate. Certain opioids, such as methadone and buprenorphine, are prescribed to treat addiction to other opioids. [4]

Prescription opioids are available in many different forms, such as tablets, capsules, syrups, patches and suppositories. [4] They can also be administered through a variety of routes, such as intravenously, orally and transdermally. [4]

Opioids work by binding to opioid receptors (mu, kappa and delta) on nerve cells in the brain, spinal cord and gut, among other systems in the body. [4] Once bound to these receptors, they send signals that alter the perception and emotional response to pain. Opioids may also produce an overall calming and euphoric effect, a slight decrease in respiratory rate, nausea, vomiting, constipation and cough suppression. At higher doses, these effects are more pronounced and last longer. [5]

Individuals who use opioids regularly can develop tolerance, which is a decrease in response to the drug. [7] This usually results in an increase in dose to achieve desired effects. [7] When an opioid is suddenly stopped, some individuals may experience jitteriness or insomnia, also known as opioid withdrawal. [4] These symptoms can vary in severity, depending on the dose and length of opioid usage. [7]

Opioid use for pain, both short-term and long-term, can predispose an individual to opioid use disorder. [8] Opioid use disorder is also known as dependence and addiction, with addiction representing the most severe form of the disorder. [8] The disorder is characterized by a strong desire to take opioids, higher tolerance and impaired control over opioid use. In 2016, there were an estimated 27 million people globally who suffered from opioid use disorders. [9]

Opioids are associated with significant adverse effects. Side effects include:[4]

More serious, life-threatening side effects occur following an opioid overdose. In 2017, opioid overdoses accounted for 66% of global deaths attributed to drug use. [10] A high concentration of opioids can cause death by respiratory depression due to the presence of the receptors in the brain stem and respiratory centers of the brain. Activation of these receptors leads the body not being able to recognize rising levels of CO2 in the blood, resulting in the body believing it does not need to breathe anymore. When this occurs, an individual’s heartrate slows and they lose consciousness. The combination of opioids, alcohol and sedative medications increases the risk of respiratory depression and death. [5,9]

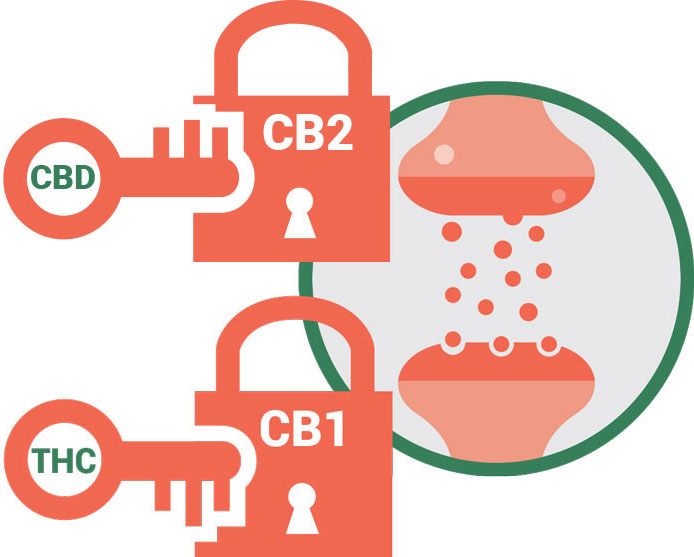

Cannabis can be an effective medicine to manage pain due to its activity on our endocannabinoid system, more specifically its interaction at the CB1 and the CB2 receptors. [6]. Did you know that we have 10X more CB1 receptors than opioid receptors (mu, kappa and delta)? [25]. The CB1 receptors are mostly located in the central nervous system (ie. your brain and your spinal cord). The central nervous system communicates pain signals from the periphery to the brain and cannabis blocks this signaling, thus alleviating pain. [6] Interestingly, cannabinoid receptors and opioid receptors are co-located in the same regions of the brain, suggesting they may produce similar pain-relieving effects. [24]

Cannabinoid receptors on the other hand, are not found in the brainstem suggesting that cannabis will not cause respiratory depression, even at much higher doses. In fact, the lethal dose of cannabis had been estimated at > 15 000 mg. [11] This would be equivalent to smoking 133 average size joints with 15% THC, which is humanly impossible. [11]

Similarly, the guidelines for chronic neuropathic pain recommend other pharmacological agents prior to the use of opioids, however, opioids only second after the first medications have been tried and deemed to be inefficient. Cannabis is recommended as third-line following opioids. [21]

Research to support the long-term use of opioids in patients who suffer from chronic pain is rather weak and insufficient. [12,13,14,15] Yet in 2018, in Canada, 1 in 5 people were prescribed opioids for long-term use. [16]

In response to concerns that Canadians are the second highest users per capita of opioids in the world, guidelines for opioid usage in non-cancer chronic pain patients have been developed in Canada.[17] These guidelines recommend all other pharmacologic and non-pharmacologic options should be tried and optimized before a trial of opioids is started. [17] Based on the safety profile and efficacy data on cannabis [6,11,18] cannabis should be moved above opioids. Cannabis has statistically been shown to be effective in the management of chronic neuropathic pain and chronic non-malignant pain. [18,19,20]

Based on the safety profile and evidence available to manage chronic pain with cannabis, would it not be safer for cannabis to precede opioids on treatment algorithms?

Emerging evidence shows that in areas where medical cannabis is available, there is reduced opioid overdose mortality. [22] A recent study conducted in Canada also found that increased regulated access to medical and recreational cannabis can result in a reduction in the use of and subsequent harms associated with opioids. [23] These studies show the duality between cannabis and opioids, and how cannabis can be a safer alternative to prevent the harmful effects of opioids.

There were an estimated 53.4 million users of opioids globally in 2017. This corresponds to 1.1 per cent of the global population aged 15–64. [7]

There is no safe dose of opioids. Harms and adverse effects can happen at any dose.

Since there are many different opioids used for the same purpose, we use morphine equivalence to compare how strong they are. The higher the milligrams of morphine equivalence, the more likely patients are to experience harms associated with opioid therapy.

Patients who receive long-term opioids can develop a tolerance to the medication. This means they require more medication to achieve the same effect. Because of this, a tolerable dose in one patient may lead to an overdose in another.